There's no shortage of people talking about AI-assisted software development right now. Your LinkedIn feed is full of it. Half the posts are breathless announcements that someone built an entire SaaS product in a weekend. The other half are selling you a course on how to do the same. What's harder to find — genuinely harder — is a plain account of what the process actually looks like when it works. Not a demo, not a thread, not a $49 workshop. Just: here's what I do, here's why, and here's what happens when I do it.

So that's what this is.

I've built somewhere north of a dozen functional tools over the past year using AI-assisted development. Task management systems, cost estimation software, contract pipeline trackers, document automation, grocery cart integrations. Some of them are in daily use. Some of them solved a problem once and haven't been touched since. None of them took more than a few days from first idea to working product. I don't say that to be impressive — I say it because the speed is a direct result of a specific process, and the process is the thing worth sharing.

The single biggest mistake I see people make is opening a code editor too early. They have an idea, they sit down with an AI coding tool, they say "build me a thing," and they get something that sort of works. It runs. It handles the happy path. Then they try to use it for real and it falls apart, because nobody thought through the edge cases, the constraints, or whether the APIs they need actually exist. So they go back and redesign, which means they're now debugging a codebase that was built on assumptions they've since abandoned. This is the loop that kills most AI-assisted projects, and it's entirely avoidable.

Here's what I do instead, and I'll use a real example to walk through it.

Start With Exploration, Not Code

A few weeks ago I was standing in Kroger, doing the same weekly grocery run I've done hundreds of times, and I wondered whether Kroger had a public API. That was the whole idea. Not a product vision, not a business plan — just a question that came from being mildly annoyed at a repetitive process.

Before I did anything else, I explored. Kroger does have a public API — product search, store locations, cart management, OAuth authentication. It's capable. But it also has limits: no access to purchase history through the public tier, which meant any design that depended on knowing what I'd bought before was dead on arrival. That's a constraint, and knowing it early saved me from building something that couldn't work.

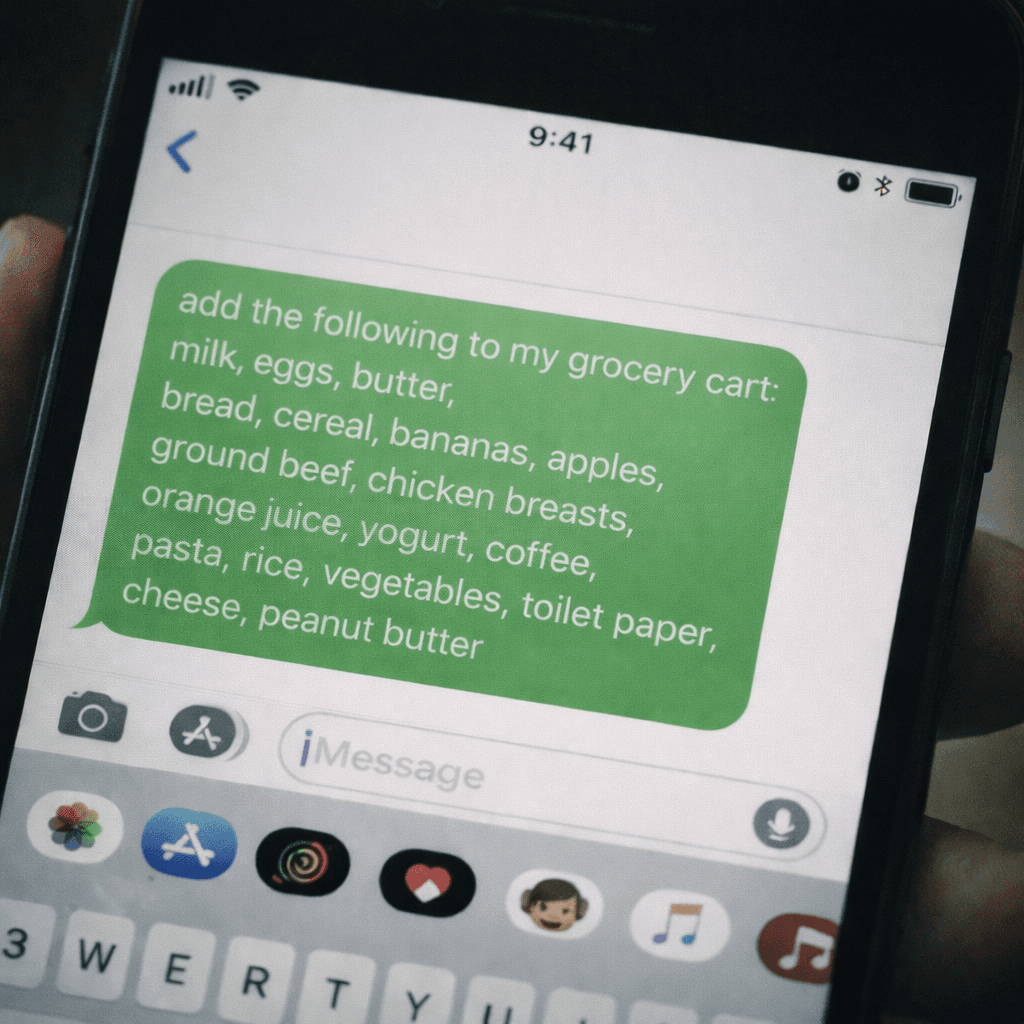

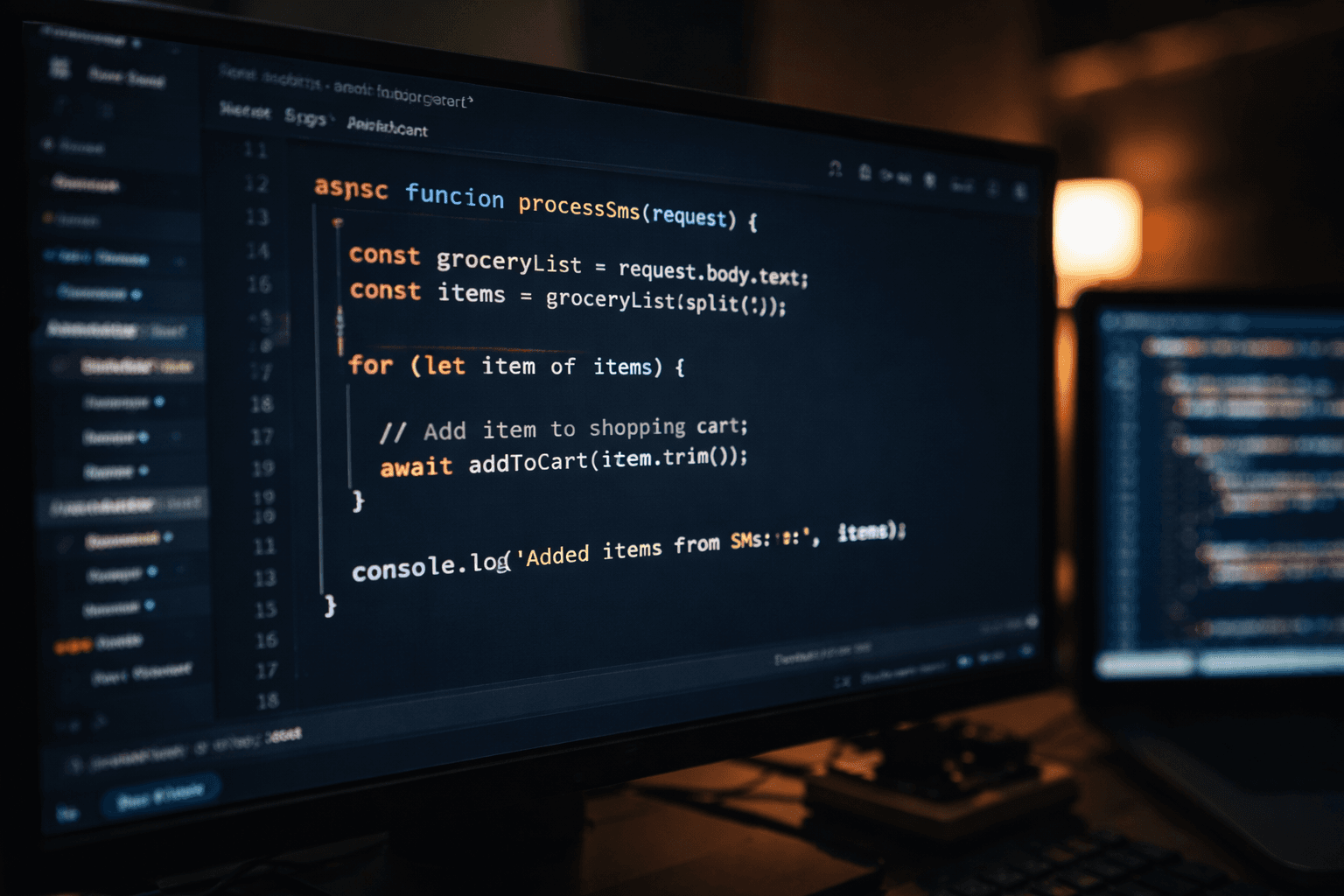

Then I looked at what I already had. I'd previously built a system where I text a grocery item to a Twilio phone number, it routes through a Claude API call that interprets the message, and the item lands on my task management app. One of those lists is a grocery list. So I didn't need to build a grocery app from scratch — I needed to connect an existing list to a new API endpoint.

Then I identified the boundary cases, and this is where things got interesting. My family has serious food allergies — the kind where grabbing the wrong brand isn't an inconvenience, it's a trip to the ER. That meant I couldn't let the system search Kroger's catalog dynamically and return whatever ranked highest. When I say "granola bars," it needs to return MadeGood every single time, because those are top-9 allergen free. When I say "milk," it means Kroger whole milk, not whatever's on promotion.

That constraint eliminated an entire category of design approaches. No fuzzy matching, no search-based resolution. Instead, the design called for a locked mapping table — a simple database where each shorthand term I use maps to one exact Kroger product UPC. Limited flexibility by design, because in this context, flexibility is the risk.

None of this involved writing code. And that's the point.

The Software Design Document

Once I've explored the idea, mapped the constraints, and understood the existing architecture, I write a software design document. Not a sketch, not an outline — a detailed SDD that specifies data models, API interactions, error handling, edge cases, and a testing strategy. The kind of document you could hand to a developer who has zero context and they could build the product from it.

I use AI to help generate this document, and the process of generating it is where the real thinking happens. Writing an SDD forces you to answer questions you haven't thought of yet. What happens when a mapped product is discontinued? What happens when the OAuth token expires at 6 AM on a Sunday? What does the confirmation message look like when half the items resolve and half don't? Every one of those questions, answered in a document, is a bug you'll never have to find in code.

After the SDD, I review the architecture against it. Does the design solve the original problem? Does it account for the constraints? If not, I change the document — not a codebase.

Then I generate a detailed implementation plan from the SDD. Ordered phases. Definitions of done for each. Dependencies mapped.

Then I code. And by that point, the coding is the least interesting part of the process. The decisions are made. The ambiguity is resolved. I'm translating a clear plan into a working product, and the AI coding tools are genuinely excellent at that specific task. What they're not good at — what nothing is good at — is making design decisions in the absence of clear requirements. That's still a human job, and it probably will be for a while.

The Real Takeaway

The Kroger project went from a thought in the produce aisle to a complete, implementation-ready SDD in an afternoon. I've attached that SDD to this article as a free download — not because the grocery automation itself is interesting to most people, but because most people have never seen what a real, detailed software design document looks like for a project built this way. If you're building with AI tools and skipping this step, you're making it harder than it needs to be.

💎 Free Download: Grocery Automation SDD

Want to see the full software design document? Download it here and use it as a reference for your own projects.

Download the SDD (.docx)And if you've got an idea you've been sitting on and need help getting from concept to something like this, send me a message. That's what I do.

Indy-Pendent Solutions helps businesses and government contractors turn ideas into working software using a design-first approach to AI-assisted development. josh@indypendentsolutions.com

Topics

Josh Parker

Founder of Indy-Pendent Solutions and flowState Software. Former Air Force combat rescue pilot, defense program manager, and capture strategist with 20+ years in defense acquisition.

Need help with your next capture?

Whether you need software tools or hands-on consulting, we can help you win more government contracts.